Archive for category 1989

Road House

A weird, incomprehensible, idiotic, and wonderful mess of a film.

The “so bad its good” movie is one of the stranger phenomena in film. I’m not sure when exactly ironic love for movies began, but I’m even more perplexed by what that kind of love really means. It is sort of like watching an overweight, uncoordinated middle-aged guy attempt to dunk a basketball but fall flat on his face while missing the dunk. (All the better if a trampoline is involved.) It is mostly hilarious, watching that guy look so inept while falling short of his goals, but there is a bit of sadness mixed in with the laughter. It is a condescending kind of love, because we are sort of celebrating failure, but that love is nonetheless sincere. We are genuinely grateful that the guy attempted to dunk in the first place.

Like most metaphors, this one is imperfect. A bad film happens not by clumsiness but a series of deliberate, and poor choices. So in “Road House,” for example, someone chose to include a bit of dialogue explaining that Patrick Swayze’s character Dalton (no last name), despite being a careerist bar bouncer, went to N.Y.U. where he studied Philosophy. (“You know, the meaning of life and all that shit.”) Another line of dialogue in comes from a chief lackey for the bad guy who says to Dalton, “I used to fuck guys like you in prison.” Someone wrote or improvised that dialogue and someone else approved their inclusion in the final cut. I’ve probably never heard a more delightfully absurd character detail nor a more psychotic and insane combination of self-aggrandization and threat. (I mean that guy was proud of what he did in prison.) What measure of madness and brilliance prompted those choices? These snippets are some of the only scraps of information we get into these characters backstories, yet they hardly explain their bizarre decisions and the baffling situations they find themselves in.

This isn’t a film that is all that interested in its characters. Even “Zen and the Art of Nightclub Bouncing” Dalton is a facsimile of a more traditional action protagonist, with his painful past and vaguely-defined Eastern spirituality which medicates it. Taking shortcuts with characterization is an old standard with action films, but usually the payoff is…action. “Road House” has mostly a dearth of action, with the occasional brief and bloody confrontation thrown in to give us just a little taste. (Someone gets their throat ripped out in this movie. Their throat!) Even the final confrontation offers little of the thrills which the film relentlessly builds to.

Instead, it meanders into a mostly incoherent plot which I suppose can be construed as some sort of parable about the power of local cartels to defeat the aggressive business tactics of national chains. The aptly named Brad Weasley (Ben Gazzara) is the oppressive business magnate who injected economic life into a small Kansas town, but not without a spiritual cost. Weasley lords over the town like the king of a very small kingdom and extorts money from all the local businesses and dictates to everyone what is what. Normally, those at the top of the economic food chain try to placate the masses in order to keep them complicit in their own oppression, but not Weasley. He terrorizes the “little guys” who don’t bow down to his authority, going so far as to take a monster truck to a car lot owned by an independent-minded auto dealer. Eventually all this posturing escalates to lethal levels, cajoling Dalton out of his pacifism, who was really only in town to clean up a local road house anyway and had no reason to get involved. Weasley could have had it all if had simply minded his own business. Why not give Weasley a coherent worldview and reasonable motivation to do what he does?

There are more weird choices in this film to discuss, including a romance involving Kelly Lynch which is more contrived then something out of “The Bachelor” and Dalton’s mentorship by Sam Elliot, but why bother? I won’t come any closer to figuring out this film’s perspective. That is, I think, really where the love for bad films come from. There is something refreshing in a point-of-view you don’t really get. “So bad their good films” are like having a friend who constantly has baffling opinions like “Culture Club is one of the top 3 bands of all time, behind only Disturbed and Elvis Presley.” You honestly can’t tell if your friend is crazy or brilliant, but that friend believes what they are saying wholeheartedly. Having those people in your life is awesome, and so is “Road House.”

4/5

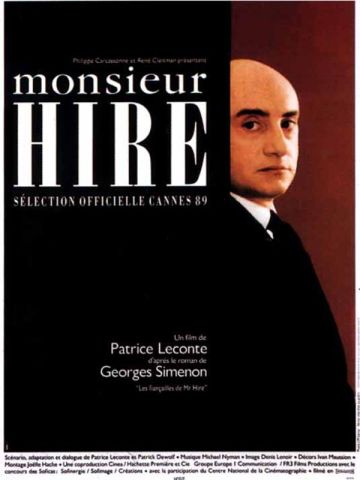

Monsieur Hire

Sexual chemistry between a middle-aged voyeur and a young exhibitionist is the best kind of sexual chemistry.

Nobody does odd romance quite like Patrice Laconte, whose authentically idiosyncratic lovers manage to find their perfect match in a world of busted and disingenuous relationships, despite the odds. The rub, of course, is that rather than the end of their problems, meeting each other usually is the start of the them. “Monsieur Hire” plays much the same, with the creepy voyeurism of the titular character meeting the wry exhibitionsim of his young neighbor, with tumultuous results. As for what does this nutty relationship means, I’m baffled.

Monsieur Hire (Michel Blanc) is one of those absurdly French creations, a man who is exceedingly odd but utterly contented in his oddness. No matter how people perceive him, he carries himself with the air of a man steeped in self-importance and dignity. A reclusive bald, portly middle-aged tailor living on his own, Hire does inscrutable things which I’m sure are wrought with some kind of meaning which is lost on me. More specifically, he has a collection of pet mice, of which he periodically picks one, kills it, and chucks into a river. Why? I dunno. Probably some kind of visceral metaphor for the futility of existence.

His female counterpart is Alice (Sandrine Bonnaire,) a young country girl living in a flat with wide open windows which curiously lack anything resembling blinds. Hire sees literally everything that goes on at her apartment, because when he isn’t working or killing mice, he just stands next to the window and stares at her, or follows her when she goes out with her dubious boyfriend/fiance Emile (Luc Thuilier.) If this sounds horrifying, it isn’t for Alice. After seeing Hire’s face in the window thanks to a timely lightning bolt on a stormy night, Alice realizes that she gets a sexual thrill from being watched by Hire. Knowing this, she begins tantalizing him in various ways, from dropping tomatoes in the hallway to having wild sex with Emile with Hire gazing at them from afar.

This “romance” plays out amidst a murder investigation in which Monsieur Hire is the chief suspect, largely because of his serial-killer vibe and lack of an alibi. Hire is too obvious a culprit to have actually done it, but the detective suspects Hire knows more than he lets on, a la “Rear Window.” Plus, like everybody else, the detective seems to genuinely dislike Monsieur Hire, and the investigation gives him a chance to harass Hire and otherwise pry into his, voyeurism and creepiness aside, rather dull personal life.

Most of this film is a mystery to me, probably because I lack the cultural and cinematic language skills to decipher it. I spent most of “Monsieur Hire” wondering what I was supposed to get out of this quasi-love triangle between a middle-aged voyeur, a young exhibitionist and her rapscallion of a fiance. These aren’t exactly relatable characters, and it isn’t as if this is a film in which you root for the “lovers” to end up together. So, mostly I just watched the film in stupor, while occasionally scratching my head. Don’t mistake me, however. This film’s strangeness is commendable, and the film oozes style and sexual energy, even if it is unseemly. Hire and Alice’s relationship is ultimately unsustainable. This is likely true for all passionate romances, but the acuity of their fetishes makes it more explicit that sexuality alone isn’t enough form the basis of a long-term partnership. Nevermind the romantic impulses which drive them towards poor decisions. Sometimes love don’t feel like it should, I guess.

3.5/5

When Harry Met Sally

My chief issue with “When Harry Met Sally” stems from the fact that I simply expect more from a modern romantic comedy classic. Perhaps this is an unfair criticism to lay on a film that is perfectly enjoyable, if perfunctory in its machinations. Nevertheless, aside from the iconic fake orgasm in a New York deli, the film never rises above artificially sweet entertainment, or the better films to which it owes a great deal.

Shooting a film in which a number of neurotic New Yorkers pontificate about their relationship troubles is always dangerous. No filmmaker has every taken that approach quite so successfully as Woody Allen, whose “Annie Hall” and “Manhattan” cast such large shadows that any films emulating them are doomed to look like pale imitations. So it is for “When Harry Met Sally,” a film which never quite lives up to the potential of its first few scenes. Carpooling after college from Chicago to New York, Harry Burns (Billy Crystal) and Sally Albright (Meg Ryan) engage in a spirited discussion about the sexual politics between men and women. (Note: I called it a discussion, but it is more accurately described as Billy Crystal espousing a number of seemingly outrageous claims and Meg Ryan acting incredulous at his audacity.) Specifically, Harry suggests that men and women can’t be friends because of the male sexual impulse to try to sleep with virtually every woman he meets.

As an opening thesis, this is really compelling. How does sex complicate non-romantic relationships between heterosexual males and females? The film isn’t really interested in the question. Instead it uses that conversation as a backdrop for a modern classical Hollywood romance. After that initial conversation, Harry and Sally bump into each other a few times over the course of the next decade, up until the point at which Harry’s failed marriage and Sally’s repeated bad relationships allows the seemingly impossible to happen: Harry and Sally…… become friends. This forms the foundation for scenes in which the two subconsciously develop feelings for each other during the course of their friendship, sleep together in a desperate moment of mutual weakness, accept that they made a mistake, before ultimately accepting that they are perfect together.

This plays out sweetly enough. I grew up in 90s thinking Meg Ryan was that cute lady in all those boring romantic comedies. I still kind of think that, but find her performance charming enough, though the script really does her no favors. She has no real character arch, nor is she given much, besides the fake orgasm, to do. Her role is mostly confined to bewilderment or laughing at the hands of Billy Crystal, who by far has the better part. At twenty, he gets to be have fun antagonizing Sally with his self-aggrandizing nihilism with regard to sex and women. Later, he develops a stone cold pragmatism about the inevitability of marriage, before becoming a brooding and heartbroken after his wife leaves him for another man. As comedically neurotic Jewish New Yorkers are, Billy Crystal is no Woody Allen, but he certainly has his moments.

The real trouble with “When Harry Met Sally” is its classical structure. Classic romance involves what amounts to two demigods discovering each other amidst of sea of mortals. Their only real dilemma is that they haven’t yet gotten together. The plot is more ritualistic courtship than compelling revelation. Front lit and glowing, so glamorous our the lovers that they literally glow at each other like mythical creatures, calling to each other. Even Spencer Tracey and Katherine Hepburn can’t seem to resemble anything close to normal human beings on while on camera. Modern romance are driven by a conflicting impulse: Relatability. The characters in modern films should be ones we can identify with. Billy Crystal, while a good looking fella, plays a bit of a schlub. Meg Ryan, while most definitely pretty, plays is more girl next door than glamor queen. Yet while the two leads don’t look so much like classical movie stars, they sure do talk like them. Every line seem to want to be larger than life. Every conversation is grandiose, every disagreement more pleasant and romantic than it ought to be. (Also, color films are at distinct disadvantage when trying to invoke classical structure. Other, better writers such as Roger Ebert go into more detail, but Black and White films look and feel timeless, whereas color films look and feel of their era.) The result is a mildly diverting film which lacks the gumption to truly recreate the films it is modeling itself after. (This film of course generated numerous copycats, most of which are much worse, but it is not really fair to judge a film for its inferior progeny. That would be like blaming “Quiet Riot” and “The Scorpions” on “Led Zeppelin.”)

Perhaps what this means is that even everyday folks can (and do) have epic Hollywood romances. Certainly the interludes of romantically bombastic cherry-picked tales from real-life couples endorses this. If that is what the film made you feel or think, fair enough. It didn’t make me feel much at all, other than frustration that the characters weren’t real enough, that the emotions weren’t enormous enough, and that the themes were mere fodder for a rather listless romance. I do admit, I laughed a few times and any film with Carrie Fischer in it will score some bonus points. Plus, by referencing it several times, “When Harry Met Sally” really filled me with the desire to watch “Casablanca” again. So there’s that.

3/5

Kiki’s Delivery Service

Reviewing a Hayao Miyazaki film is an exercise in utter redundancy. You start by acknowledging the sense of whimsy and wonder that pervades whichever of his films is being discussed, paying special attention to its casual insertion of magic and fantasy into everyday life. For “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” this takes the form of a thirteen-year-old witch (named Kiki as per the title) that is able to fly on a broom (or quasi-brooms) and talk to cats. Next there should be some chatter about how Miyazaki eschews the narrative structure of most American films, with no antagonists to speak of and relatively minor conflict, of which most is of the common everyday variety of drama. Again, that applies here, in which young Kiki, on a magical walkabout of sorts as a rite of passage for witches, starts a delivery service in which she has no rivals, no competition, and meets generally nice and helpful people that help her achieve her goals, with the possible exception of one teenage girl whose greatest transgression is to make a rude comment about her grandmother’s cooking. Finally, there should be some discussion of the film’s themes, whether they be overt or otherwise. In “Kiki,” that would be the conflict experienced by adolescents between embracing the impending responsibilities of adulthood and clinging to the last vestiges of that joyful freedom of childhood, along with some tension between the desire for independence and the need to rely on others.

Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately for an amateur film blogger, “Kiki” has one key distinction between it and the rest of Miyazaki’s films: Visually it suffers from a serious lack of whimsy, magic and wonder. In this, it is somewhat the inverse of “Howl’s Moving Castle,” a film which is an absolute visual feast but which has a narrative that struggles at times with basic coherence. “Kiki’s Delivery Service” has none of those problems, but is woefully bland to look at. This is of course relative to Miyazaki’s other films, as in general the animation is quite good and the film is substantially more interesting then of most of the films of Dreamworks. Miyazaki has established such a high standard for himself, a couple of his films will doubtless be unable to live up to them.

It must be said though, as a film for pre-teen girls, “Kiki’s Delivery Service” is among the best I’ve seen. In it Kiki, voiced in the American version by Kirsten Dunst, leaves her parent’s house in the country on her thirteenth birthday so that she may spend a year as an apprentice elsewhere. Excited, she finds her way to a giant city, but she soon finds herself overwhelmed. Luckily, she meets a kind baker that is willing to give her a place to stay and provide help in starting her delivery service. She befriends a nice elderly customer, is pursued romantically by an exuberant boy that is an avid fan of flying, and gets in a couple of thick spots with her sassy and sarcastic cat, voiced by the legendary Phil Hartman.

The importance of a film in which the teen female protagonist is never rewarded for being attractive, has a brain, and does not do anything at the end of the film that she was incapable of doing at the beginning of the film, but she nevertheless ends the film a hero, should not be understated. There is not a malicious bone in this film’s body and there simply are not mainstream animated films in America that are made like this. Of course, there absolutely should be. It’s just that I’ve become a bit spoiled with Miyazaki films. When I’m watching one and I’m not filled with awe, not captivated by the characters, however sweet and earnest they may be, and dare I say, a little bored, I can’t help but be disappointed. That might not sound like much of an endorsement for the film, but in a weird way, it really is.

3.5/5

National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation

I’ll admit it. I’m a bit of a Grinch when it comes to Christmas films. With a few exceptions, so tired and lazy they all are while simultaneously ramming the importance of their WASPy and middle class version of Christmas down our throats. It’s like being yelled at by a fascist decked-out in green and red and lying on a hammock. “Christmas Vacation” seems like a film poised to explore the less glamorous aspects of Christmas, like family stress brought on by feuding relatives or the general holiday performance anxiety fueled by pressure to have a “happy holiday,” and in so doing ridicule Christmas films themselves. Instead, all the film can muster is an obscene amount of pratfalls by Chevy Chase, whose constant mugging for the camera is an insult to the fine folks in the world that make a living by robbing people on the street.

Chase plays Clark, the ineffectual patriarch of the Griswold family. The paragon of the modern movie Dad, he compensates for his lack of power at work by tyrannically insisting that everyone have a great Christmas, despite the fact that nobody seems all that interested. Woefully inept, his kids Audrey (Juliette Lewis) and Russ (Johnny Galecki) just sort of tolerate him while his saintly wife Ellen (Beverly D’Angelo) is endlessly supportive, if a little concerned. His in-laws are the only ones that seem to recognize him for the moron he truly is.

Rather then take place in some sort of universe which resembles our own, the film exists in an alternate dimension, free of real consequences, both physical and legal. This enables Chevy Chase to fall, break windows, get struck by blunt objects, and otherwise endure all sorts of physical misery, without the troublesome visits to a hospital. It also allows Clark to decimate the home of his next door neighbors, whose only crime is being new age yuppies that don’t really celebrate Christmas, in a recurring series of mishaps that go unimpeded, by either the neighbors or the law.

There are a couple of laughs in the film, but they come almost exclusively from an exasperated Clark going on a tirade against the forces that would oppose his obsessive Christmas dream. Instead of generating insightful humor from the Griswold’s extended family, the film largely ignores them. Clark and Ellen’s parents are virtually indistinguishable. Only the seriously addled Aunt Bethany (Mae Questel) sticks out, mostly because of her horrible dementia. I was merely embarrassed for Randy Quaid, who plays Clark’s boisterous and grating cousin Ed.

Chevy Chase has been doing this sort of thing since he first burst onto the scene in 1975 on Saturday Night Live. Clark Griswold is really just a variation on his Gerald Ford character from back then, only it was even less funny 14 years later. If Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton are the high water marks of physical comedy, Chevy Chase stands at the opposite end of the spectrum. Merely falling from a ladder and making a silly face is incredibly lazy and not the least bit funny. In a world that contains the film “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles,” can “Christmas Vacation” really be taken seriously as an endearing Christmas comedy classic?

1.5/5

Sex, Lies, and Videotape

Posted by bslewis45 in 1980s, 1989, Drama, Steven Soderbergh on 26/11/2012

The title of this film suggests it is about the intersection of sex, lies, and videotape, and to a certain extent, this is true. However, the film seems far more concerned with honesty, then dishonesty. The camera pierces through the social mores and niceties of white middle class suburbia, laying bare the unsustainable psychological foundations upon which the character’s flimsy relationships are based. While the appeal of sex often resides in the mysterious engagement with the “other” or in the sheer illicitness of the act, this film suggests a powerful intimacy made possible through sex based on a frightening kind of pure and raw honesty.

The film centers itself on the listless marriage of John and Ann Mullany. It is a loveless marriage of convenience in which John (Peter Gallagher) is able to appear the part of a happily married man, and Ann (Andie MacDowell) is granted a comfortable life as a housewife, while neither of them seems to derive much happiness from sharing their lives with each other. Ann’s life is empty and shallow, in the way that it would be someone that is desperate to be out in the world but is trapped in their home doing housework. Ann and Peter very rarely have sex, that is to say, with each other. Ann does not much care for sex, but John loves it, just, not with Ann. John, no stranger to an active sex life with multiple partners, is in midst of an affair with Ann’s sister, Cynthia (Laura San Giacomo). As sisters, Cynthia and Ann have the kind of relationship in which they define themselves as the opposite of each other, pushing each sister further and further towards extreme personalities. Hence Ann is a shy, prim and proper prude and Cynthia is an outgoing, blunt sexpot.

Enter Graham (James Spader), John’s former college roommate, who stays with the Mullanys for a time. In the years following college, Graham has become a sort of artsy, Bohemian vagabond, with the requisite dislike of conventions, including possessions and pretense, etc… Graham also brings with him a video camera and a series of tapes of women he has filmed talking about sex. Graham is a voyeur, whose only means of sexual satisfaction comes from watching women’s intimate, recording confessions. Ann finds herself drawn to Graham’s honesty and general oddness. Needless to say, Graham’s appearance stirs things up in the Mulany’s quiet life in Baton Rouge.

The presence of the camera stands in for film’s extremely male view of women’s sexuality, exploiting them as sexual objects to be admired or earned. In Sex, Lies, and Videotape, the camera is like a psychological predator, stalking its prey in the hopes of discovering some secret scrap of information. When the tables are turned on Graham, he is clearly made uncomfortable by the presence of the camera, which turns him into the subject and forces him to become the object of deconstruction and self-analysis.

If the film has one flaw, it is the character of John, who it must be said is simply an all-around scumbag. As the lone principal character that is not filmed by Graham’s camera, he is not afforded any sort of arc like the rest of the characters. Rather, as a lying, cheating jerk of lawyer, John is punished for his sins. It would not have hurt to make John the tiniest bit sympathetic or complex. Perhaps this is in retribution for film’s decades long mistreatment of women.

More of this film’s positive impact on independent film-making can be said elsewhere, but I find this film’s placement in the career of Steven Soderbergh intriguing. If you mixed up all of his films and showed them to someone who is unaware of their order or release, could they figure out which films came first? Such is the quality and distinctiveness of Soderbergh’s films that I do not think they could. Soderbergh remains the most enigmatic of film-makers in terms of both genre and theme. He seems genuinely bored with a kind of film once he has made it. (With the exception of the money-generating “Ocean’s” films.”) Whichever of his films I see next, I am sure it won’t be a drama about sex, lies, and an unhappy marriage.

Drugstore Cowboy

Whether it means to or not, this film makes a career of stealing drugs from pharmacies seem like the good life. Yes, I am aware that the characters in the film are harassed by the police, beaten, almost arrested, and that one even dies of an overdose. None of that changes the fact that this film is about a group of people that sustain their drug habit, and indeed their lives, by successfully robbing pharmacies. This strikes me as the point, as a drug addicts only real concern is the next time they can get high. It is just odd to see people so proficient at being drug addicts.

Bob (Matt Dillon), Dianne (Kelly Lynch), Rick (James Le Gros), and Nadine (Heather Graham) are four twenty-something junkies that form a drug-robbing team in Portland, Oregon. Bob is the ringleader of the group. He plans out the robberies and he divides the drugs up afterwards. Dianne is his wife and lifelong co-user. The two are just the kind of people for whom drugs have always had an appeal. The two have been using since they were kids, but Rick and Nadine are relative newcomers to the drug addiction game.

Due to the ramshackle manner in which they steal drugs, their lives are very much a series of hot and cold streaks, much like a game of craps. For example they score big and steal medical-grade cocaine, while other times they just get stool softener. Bob is even superstitious like a gambler. He believes in hexes, which occur when dogs are mentioned or hats are placed on beds, and which must be outrun. The group does not much care what they get so long as the substantially effects brain chemistry and/or has some market value.

The group is pursued by an obsessed detective named Gentry (James Remar) who has one of those intriguing relationships with Bob in which he knows Bob is guilty, but can’t quite catch him in the act. The two have known each other a long time. Gentry even gives Bob a little pep talk later in the film. However the crew is riding a hot streak and Bob is rather easily able to stay one step ahead of Gentry, and the film is not interested in using that relationship to generate tension. It is more interested in the psychology of a drug addiction then in being any kind of thriller.

Gus Van Sant, a director whose filmography I need to delve into more deeply, achieves success with a rough and gritty visual style that shows promises of things to come. There is a genuine understanding here of what it means to have ones life revolve almost exclusively around drugs. Unfortunately, I was rather ambivalent about these particular drug addicts. I didn’t wish them success, failure, happiness, or sadness. Perhaps this is the response people typically have to drug addicts. Some parts of the film ring false, especially a small role for William S. Burroughs as an old priest/drug addict which struck me as rather gimmicky, but the film by and large understand that a drug addict’s life is a pretty black and white. Get high and everything is fine. If your not high, get high as quickly as possible. That’s as complex as life gets for a junkie.

3.5/5

My Left Foot

I do not wish to belittle the rest of the cast of this film, which contains many very good performances, but it is impossible not to acknowledge the exceedingly brilliant performance by Daniel Day-Lewis in such a way that it overshadows everyone else involved in this film. Day-Lewis has given many great performances, but portraying novelist Christy Brown, who lives with Cerebral Palsy, is perhaps his best. While I was consciously aware that it is Daniel Day-Lewis acting, I completely lost the actor in the role.

Starting with a reception in his honor, this film tells the story of Christy Brown, through flashbacks from his autobiography. Christy was born in Dublin in the early 1930s. For the first ten years of his life, his family believed him to be mentally disabled, until, with the use of his left foot, his only fully functional appendage and what he uses for almost everything, he spelled the word mother in chalk on the floor of his family home. For the rest of the film, we follow Christy as he struggles, not so much with his disability, but with the pains of life, in particularly with love.

The film covers his adolescence and early adulthood, as he enjoys life, discovers women, paints, and becomes a famous writer. Christy is part of a large Irish-Catholic family, teeming with life and people who care about him. His family does not abuse him, though in perhaps the funniest moment of the film, his brothers hide a dirty magazine under him while he is in a wagon, which results in a lecture about sin from a priest when his parents discover it. Christie does not shy away from conflict, as he gets into several fights. He is, in the simplest of terms, a tough, hard-drinking Irishman that happens to have cerebral palsy.

The pervading disappointment in his life is his perpetual loneliness. Christy is able to handle the physical limitations brought on by his disability, but he cannot handle the loneliness it causes. When he falls in love with a cerebral palsy specialist who does not reciprocate his feelings, he is devastated. Only his mother, played by Brenda Fricker (who I know best as the pigeon lady from Home Alone 2), is able to bring him out of it. The film ends happily, with Christy finding the life partner he has long dreamed of.

Everything about this film feels authentically Irish, from the scenery and landscape to the acting, thanks in large part to the great ensemble cast. This is Day-Lewis’ film, though, and it works because he completely brings the character to life. Never did I think I was watching an actor pretend to have Cerebral Palsy. I felt I was watching the character Christy Brown. I do not know how many other actors could have pulled off a role like this, but there cannot be very many. This film does not shock or challenge, but it does inform and entertain, which I believe is want one would want from an autobiography about an Irish writer with Cerebral Palsy who learns to do almost everything with his left foot.

3.5/5

Arena

Posted by bslewis45 in 1980s, 1989, Peter Manoogian, Science Fiction on 17/10/2011

This is a film perfectly suited for the “B Movie” scale. It has cheesy special effects and acting, and I cannot imagine anyone on the production felt that they were making a “good” film. It is a rip-off of several legitimate films, with several poorly handled cliches. In other words, this is a really unintentionally entertaining film, though not among my favorite B movies.

The plot more or less is a combination of Star Wars and . There is a human named Steve Armstrong (Paul Satterfield) who dreams of being a champion in…The Arena. The Arena is this boxing/sumo wrestling ring, in which alien fighters win by kicking/punching/throwing each other outside of it. It has been 50 years since a human has fought. This is literally everything you need to know. There is a horned, steroid junky alien champion, who works for a white, pony-tailed tool, who looks like a pedophile. Also employed by the evil businessman is a cronie named Weezil who looks like a weasel.

Helping Steve out is a four-armed alien version of Mickey, who comes complete with that same raspy voice and Quinn the owner of a gym whose father was in it for the love of the game but got pushed out by the evil businessman. Quinn sadly carries on his dream in a corrupt world. There is also Jade, who attempts to move between the evil group and the good group. Jade seduces Steve and tries to poison him, but also has feelings for him. Mainly she is there to be the hot chick that the hero rejects when he realizes she is shallow/lame/evil.

So there are a number of nice touches in this film. Lots of absurd aliens walking around, some weird future nightclub singing, and a couple of hilarious deaths. Some of the fight sequences are quite awkward, as Steve fights non-humanoid aliens. I was surprised that there were no montages in this film. Steve starts out awesome and just kicks ass. He requires minimal training. The only time Steve sucks is the dramatic final fight between the steroid taking goat man, who I believe was called Horn. Steve struggles because Weezil and another character named Skull rig the handicapping system. The handicapping system is this series of lights capable of weakening an alien’s strength to even out the match. The film informs us that no one has ever been able to crack the handicapping system in the hundreds of years it has existed, but Skull and Weezil have no problems.

The film is also pretty indecisive with what it wants to do with Steve. On one hand, they want to make him the reluctant hero. On the other, he has wanted to fight in the Arena all his life. In this respect, it is odd when he turns down Quinn’s offer to fight in the Arena. The special effects in this film are surprisingly decent and at times, it teeters on the edge of being a legitimate film. However, most everything else is mediocre to terrible. Despite this, it was a pretty entertaining film. I’m glad it caught my eye on Netflix and I believe my life is at least nominally better now that I have seen it. (P.S. Looking at this director’s filmography, there are other classics that need to be seen. I am proud to say I have already viewed one of his other films.)

3.5/5 (B Movie Scale)

Santa Sangre

I cannot, in any way, conceive of anyone but Alejandro Jodorowsky directing this film. It is a wonderfully bizarre mix of horror, humor, surrealism, and other flavors that only Jodorowsky can bring to a film. This film surprised me with its beauty and its ability to pull me in. I was also unprepared for how easily the film switched from dark comedy to tension and terror. This is a film I want to see again, but perhaps not for awhile.

Describing the plot of a Jodorowsky film is somewhat an exercise in keeping a straight face. His film plots can be nonsensical or ridiculous. This film, however, has a relatively straight forward narrative arch, even if the film is extremely outlandish. The film begins by showing us Felix (Axel Jodorowsky) looking like Jesus, but naked, next to a tree in a mental health facility. There is a tattoo of a phoenix on his chest. Through a flashback, we will come to learn how Felix got that tattoo, and how he ending up in that mental hospital.

Felix grew up in a circus in Mexico. His father, a knife-thrower, was also the owner of the circus. His mother uses her hair in a trapeze act. His upbringing was more than a little unusual, and his mother and father were something less than model parents. His mother, Concha (Blanca Guerra) is a member of an unauthorized offshoot of Catholicism. The film shows us a little shack that is about to be bulldozed. Concha is one of the women protesting and standing in the way of the bulldozer. When a member of the Catholic Church arrives, he is shown inside, where Concha explains that a woman was raped and her arms were torn off at the very spot they were standing, and the red pool in the temple is her blood. The religious official is less than convinced that that woman was a saint, and gives the bulldozer permission to destroy the “temple.”

Felix’s father, Orgo (Guy Stockwell) is a drunk, but more importantly, a lech. When Felix cries over a dead elephant, his father carves the phoenix into his chest. When a tattooed woman who appears to be lust incarnate comes on to his father, his father is more than a little enticed. Concha tries to dissuade the tattoed woman from pursuing her husband, but that fails, so Concha throws acid on her husband’s genitals, who then cuts off her arms and slits his own throat, in front of Felix.

Felix’s experience was not all bad at the circus. There are a number of clowns and dwarf who are his friends. There is a girl there, the deaf and mute adoptive daughter of the tattooed woman, who has a sweet relationship with Felix. All that goes away though, when he parents more or less kill each other. He spends a good deal of time at the mental health center, but when given a trip to the movies, Felix and his compatriots at the center are taken on a side trip by a pimp that takes their money as payment for the use of his fat prostitute. While there, Felix sees the tattooed woman, and his mother arrives at the mental health center shortly after, and they begin an intimate relationship in which Concha has command of Felix’s arms.

If the plot sounds over-the-top, it is even more so depicted in the film. Uncomfortable, absurd, or sexual transitions and metaphors riddle the film. In one scene, when Felix’s parents are having sex, the climax is transitioned with an elephant trunk spewing out blood. When Felix sees a woman he is attracted to, a giant snake crawls out of his pants. There is gore aplenty, almost to the point of comic, b-movie effects. There is strange humor in the film, as when the pimp attempts to give people with down’s syndrome cocaine. The film is discomforting and engrossing all at the same time.

While this is not a film for everyone, or perhaps not even for most people, it is nevertheless a great film. If I have done an inadequate job of describing this film, please forgive me. It is a difficult film to describe. It is a unique kind of film from a unique director. It is not a comfortable film to watch, but the artistry is undeniable. A mix of Bunuel, Hitchcock, and B-Movie Camp, this film has great direction, set pieces, and that undefinable Jodorowsky factor.

4.5/5